As a Mustard Seed: Is there 'Healing in the Atonement'?

Holiness; healing; power; prosperity....

They are two quite separate questions.

Does Jesus heal today? ... and

Is provision for healing made in the Atonement?

Most Christians, despite all the actions of 'healing' charlatans over the years, would answer the first question in the affirmative — even if they would differ considerably among themselves as to how this would look in practice.

As to the second question, a good many would be puzzled as to exactly what was meant. For them, the very phrase sounds esoteric, or obscurely theological — which is odd, because the constituency for the answer 'yes' tends to be among the less intellectual kinds of Christian.

So what does 'healing in the atonement' mean?

It is the idea that, just as the crucifixion of Christ was for forgiveness of our sins, so it is also for healing of our diseases. Just as we can be sure that God wants "all people to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth" (1 Tim. 2:4), so He definitely wants you to be healed.

It follows — blessedly or ominously, according to your point of view — that, just as you can have assurance that your sins are forgiven if you trust in Christ ... so your healing is applied by your faith.

Ahhhh. That'll be where the snag is. The fact that, after my lifespan of ... ohh, several centuries, I still have the chronic eczema I was born with (to say nothing of my more recent acquisition of back problems) is a fair indication that I do not have sufficient faith. Or I'd be healed.

And the same must go for so many of my nearest and dearest, who suffer from (and some of whom have died from) conditions many times worse than my own, relatively trivial afflictions.

But soft! Surely, this is going too fast.

We are making the truth or falsehood of a proposition dependent on our feelings about it.

All of us —me especially — are exquisitely good at rejecting beliefs that leave us looking bad, or deficient. Never mind if I or my friends are left exposed as having insufficient faith! What if 'healing in the atonement' is actually true?

Or rather (to keep our secular friends reading this for a moment or two longer) what if it's actually what is in the Bible?

Well...

Let’s try a quick ‘Bible study’:

a)

Isa. 53:5 “He was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was upon him, and by his wounds we are healed.”

"By his wounds we are healed."

Isaiah 53: the whole chapter is all but universally understood among Christians as a prediction — or, at the very least, a foreshadowing — of the sacrifice of Christ on the cross. If that understanding holds, then it seems that Christ's wounds are that by which "we are healed".

There is (but you were expecting this) a problem with such a reading. The verse is just one of countless examples in the wisdom literature and the prophets (and most especially in the Psalms) of the standard form of Hebrew poetry. This does not 'rhyme' in our sense; rather, the second line echoes, using different words, the thought of the line before it. The same or very similar meaning is restated.

Consider Psalm 24:3-5

"Who may ascend the mountain of the Lord?

Who may stand in his holy place?

The one who has clean hands and a pure heart,

who does not trust in an idol

or swear by a false god.They will receive blessing from the Lord

and vindication from God their Saviour."

This pattern being what it is, the expression “by his wounds we are healed” might best be understood as a mere variant of "the punishment that brought us peace was upon him". (And "punishment" for what? The answer is clear: "transgressions", and the echoing "iniquities", are in the previous line.)

If so, this is about sin — not sickness.

But if, instead of being an exact restatement of the previous phrase, “by his wounds we are healed” is made to be a different-but-related statement, then Christ’s wounds do indeed heal our (physical and psychic) diseases. In which case, healing is in the Atonement, just as forgiveness for sin is.

b)

1 Pet. 2:24: “He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree, so that we might die to sins and live to righteousness; [and then the sudden inclusion of Isa. 53:5] by his wounds you have been healed.”

Here, "by his wounds you have been healed" is clearly taken as being another way of expressing the atonement for sin. On this evidence, the phrase emphatically refers to sin, not to physical sickness.

The debate is not quite closed, however, because...

c)

Matt. 8:16b-17 appears to be a ‘clincher’ for the healing-in-the-atonement case:

“He drove out the spirits with a word, and healed all the sick. This was to fulfil what was spoken through the prophet Isaiah: ‘He took up our infirmities, and carried our diseases.’”

That, again, is a reference to Isa. 53:5.

And just as in 1 Pet. 2:24 it was obviously a reference to sin, this time it is equally obviously a reference to sickness!

However — and I think this is the decisive point (even though it leaves wide open what to make of the evangelists’ uses of OT Scripture) — precisely this passage shows it cannot refer to the atonement. For these exorcisms and healings take place before the crucifixion has happened! So, allowing the application of Isaiah to these healings to be appropriate (and the fact that it is in Matthew permits us to do no other), the healings themselves cannot be a consequence of an event that has not yet taken place, namely the Atonement. They must be down to the sheer power and authority of Jesus in His own person.1

Origins of the doctrine

The doctrine of 'healing in the atonement' arose among late-nineteenth-century Holiness evangelicals. The direction of thought it embodies (We are justified by faith; therefore the other good things that God can do are ‘claimed’ by faith also) comes specifically from Phoebe Palmer, an extremely influential Holiness preacher from New York City.

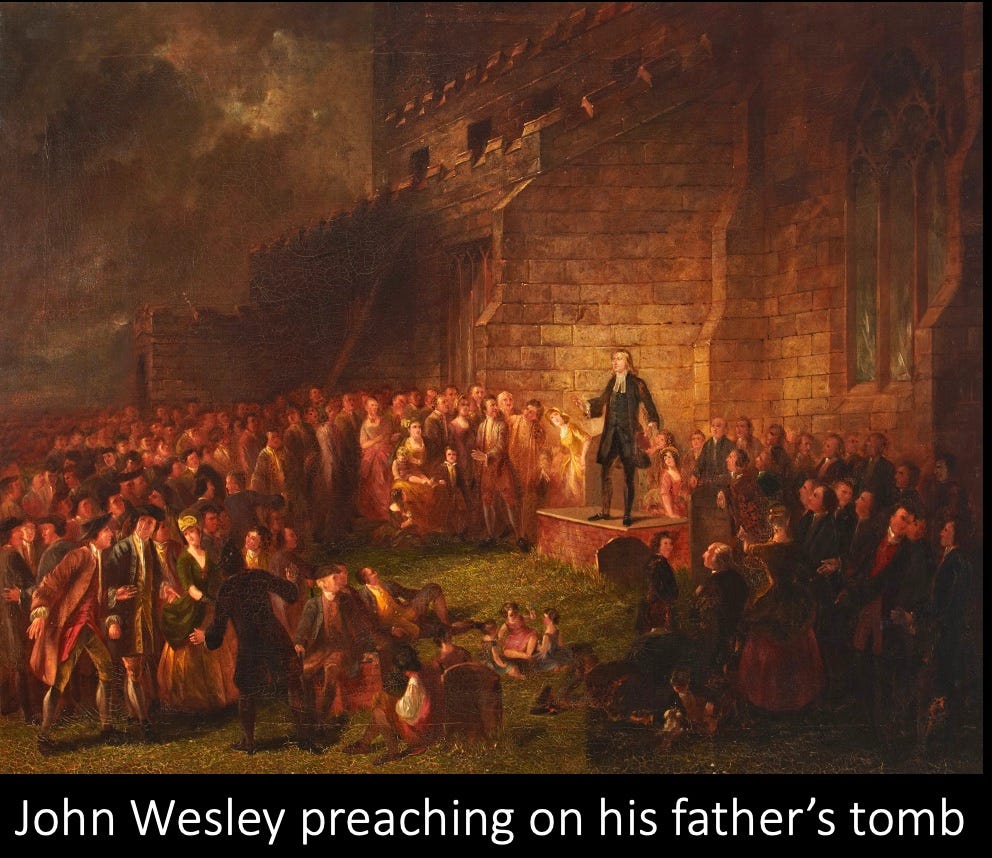

The Holiness movement taught ‘entire sanctification’. (That is the idea that a Christian can — not will, but can — live a life experientially free of committing sin. Though, to be sure, the doctrine was hedged about with all manner of ifs, buts, and qualifications.2) Several generations earlier, ‘entire sanctification’ had gained its importance principally through the influence of John Wesley. It is at least arguable, however, that this teaching — though certainly not the actual phrase — goes back to the Early Church. And the biblical arguments in favour of it are more formidable than its detractors allow — even if they rest on a narrow base, rather than on the general tenor of Scripture-as-a-whole. (To derive a meaning of 1 John chapters 3 and 4 very far distant from that which Wesley found there remains ... challenging — as Reformed authors of Bible commentaries occasionally demonstrate to our general merriment.)

Methodism and its associated movements dominated evangelicalism in the nineteenth century, and transmitted the teaching of ‘entire sanctification’ to an ever wider number of people; collectively, the Holiness movement was as big a slice of evangelicalism in 1900 as Pentecostalism and the charismatic movement were by 2000.

In the process of growth, Holiness doctrine became increasingly diverse, as now one, now another leader placed some particular angle upon it. By the 1830s, many Holiness people saw ‘entire sanctification’, not so much as a process that could be completed in this life, as a decisive act of consecration, a ‘Second Blessing’ that came after conversion. Many used the NT term ‘Baptism in the Holy Ghost’ (does this expression sound familiar?) to describe it.

And Phoebe Palmer’s distinctive contribution was to say that this ‘Second Blessing’ or ‘Baptism in the Holy Ghost’ did not come by striving — nor by some sovereign act that God wrought upon this person rather than that one — but by the faith of the person who sought it. “If you have faith to be [entirely] sanctified, then you are sanctified.”

It was all part of an increasingly 'supernaturalist' turn in nineteenth-century evangelicalism:

a) miraculous, instantaneous, entire sanctification;

b) dispensationalism — the expectation of a 'rapture of the saints' and an any-moment return of Christ;

c) 'faith missions': mission organisations that refused to tout for funds, trusting God to meet their needs by moving the hearts of individuals to give (such as Hudson Taylor's China Inland Mission, which was financed along precisely these lines).

And as the healing movement began to take off in Holiness circles in the late nineteenth century, so the same logic was imported to that issue in turn. If you have faith to be healed, you will be healed. It was not merely that ‘Jesus heals today’ — but that provision for healing had specifically been made in the Atonement.

Just as the person who was still in his sins was in such a state because he had no faith in Christ’s forgiveness, so the unhealed person had not appropriated Isa. 53.5b to their own case by a ‘positive confession’.

Fundamentalism, Pentecostalism, and the 'faith' movement

The wresting free of the second half of the verse "by his wounds we are healed" from what precedes it, along with ignorance of how Hebrew poetry worked — or else a decision to remain in ignorance: all of this was part of the mindset that was fermenting within late-nineteenth-century evangelicalism and would, in the early decades of the twentieth century, produce fundamentalism.

It entailed a decision to ignore context and literary form in favour of literalist readings of the text — or, more realistically, of favoured phrases wrested from the text. Supposedly, this was a defence against theological liberalism and modernist criticism of the Bible; in fact, it was a taking of refuge in obscurantism and anti-intellectualism.

(A much-needed digression:

'Fundamentalism' is, of course, one of the most abused words in the language — along with 'fascism', 'racism', ‘communism', 'totalitarianism' and — in the mouths of authoritarian governments — 'terrorism'.

It does not mean teachings more 'conservative' or principle-ridden than the person speaking happens to like.

It does not mean an addiction to outdated patterns of dress or social mores — though, to be sure, many actual fundamentalists use their doctrine as 'moral' cover for that.

a) It does not legitimately apply to anything outside of Protestant Christianity.

b) It is, its own protestations notwithstanding, distinctively modern.

c) It applies specifically to some — but by no means all — evangelicals.

d) It refers to an insistence upon a literalist reading of the biblical text (regardless of genre or, frequently, of context) — and especially of the early chapters of Genesis.

The pursuit of consistent literalism is impossible, of course.

It is easily dismantled. (Which is precisely why Dawkins and co. always argue as though 'fundamentalism' were synonymous with 'Christianity'. Straw men are the easiest targets for demolition — though the disingenuous strategy is hardly exclusive to the New Atheists.)

My own favourite (because quick) dismantling exercise for students was, when looking in class at Acts 2 [for entirely different reasons], to read out Acts 2:5: "Now there were staying in Jerusalem God-fearing Jews from every nation under heaven." And I would then add, by way of 'elucidation', "New Zealand; Japan; Guatemala; Namibia...".

The looks I had from the students were ... pretty much what I expected. So I would continue: "It doesn't mean that, does it? ... So why foist upon Scripture — any part of it — a literalist, dumb meaning that clearly forms no part of the author's intention?"

Author's intention. It goes against the grain, not only of fundamentalists and New Atheists, but of postmodern 'reader response' theory, too. There is nothing for it, if we wish to know what is going on in a text — the Bible or anything else — but to understand what the author meant and why. Goodness! Recognising that could revive the whole discipline of literary criticism!)

There. I'm glad I got that off my chest.

I feel better now.

Now — where were we?

Ah, yes. The next metamorphosis of the faith-for-healing idea.

Many Pentecostals, when that movement in turn came into existence after 1900, went on to apply the same logic to their own emphases. Their own version of ‘Baptism in the Holy Ghost’ (not so much ‘entire sanctification’ as Holy-Ghost-empowerment-as-evidenced-by-speaking-in-tongues) was to be claimed, they taught, ‘by faith’. But many of them also continued to cling to the healing-in-the-atonement doctrine that they had inherited from the late-nineteenth-century Holiness movement from which most of them had emerged. Indeed, 'healing in the atonement' remains today one of the ‘fundamental truths’ of the Assemblies of God denomination.

The period from the 1920s to the 1970s saw a flurry of 'faith healers', few of whom lived uncontroversial lives.3 (Though Oral Roberts was one of several noble exceptions.4) Some were downright scandalous — while others, like William Branham, were complete heretics.5 In the end, the movement largely discredited itself and (in the global north, at least) declined — though it still maintains a diminished existence. All were part of the more general phenomenon — from which we are, sadly, still not free — of meeting as spectacle; faith as emotional entertainment.

Not only this but, from the 1920s onwards, the new ‘health and wealth’ teachers, some of whom came from methodistic backgrounds and many more of whom were some variety of Pentecostal, would make the same 'faith' claims about personal prosperity. Name it — and claim it. Confess it — and possess it. (Blab it and grab it, we detractors say....)

So what’s the problem here?

a) Trust in Christ for forgiveness of sins — and you are forgiven.

b) Have faith to be sanctified — and you are sanctified.

c) Confess your healing (since it is in the Atonement) — and you will be healed.

d) Have faith (as evidenced by giving to my ministry!) — and God will prosper your finances.

Surely, if a principle applies, a principle applies?

The fallacy with this argument is that a ‘principle’ does not apply. God is not manipulable, nor is ‘faith’ a technique to achieve our ends. Nor is Scripture reduceable to 'principles'. (Goodness! Only modern Westerners could ever assume it was.) Insofar as there is a ‘principle’ at all, it can apply only to what Scripture indicates — which certainly doesinclude a), and certainly does not include d).

Personally, I think b) doubtful, and believe c) to be an unnecessary extension of the much simpler insistence that Jesus does indeed heal people today.

No need to shout! A soft landing....

Indeed, in the very earliest — one might almost say embryonic — phase of the charismatic movement in the 1950s (i.e., when Pentecostal practices spread to non-Pentecostal denominations), it was healing that turned out to be the 'easy way in' for some Christians. Agnes Sanford (1897-1982) and her husband, Episcopalian minister Edgar Sanford, founded the Order of St. Luke and led small conferences on healing, which proved a fruitful seedbed for spreading charismatic experience more generally among their fellow-Episcopalians and others.

This might be thought highly counter-intuitive. 'Speaking in tongues' might be thought an easier starting point. After all, it might, or might not, be faked. A 'prophecy' might, on closer inspection, be nothing of the sort. But a healing — leaving aside the disingenuous antics of platform charlatans — either happens, or it doesn't.

However — and this returns us to the point we made at the outset — relatively few Christians would deny that God can heal. So if your friend on the other side of town is sick — well, you pray for them. Very well: how about you and I go over to that person's house and pray for them there?

After a moment's hesitation (it feels odd) you agree.

So now we're there. In the house. The patient's Mum ushers us into the front room and brings us tea.

How about we actually go into the same room as our friend, where he or she is lying, sick?

...

OK....

Now we're in the room. How about one or both of us lay our hands on the sufferer's head as we pray?

And ... boom! There we are. Healing, right? It will either happen, or ... maybe it won't.

It is quite another matter, however, to proceed from there to screaming and shouting at some poor sick person, or even pushing them about, on a platform in a 'revival hall'. That has everything to do with the cult of the 'heroic leader' and our pathetic addiction to meeting-as-spectacle — and nothing whatever to do with the New Testament.

In sum:

Is there is 'healing in the atonement'? Probably not.

But can Jesus, nevertheless, heal today? Course he can.

The fact remains, however, that this is a very perplexing use of Hebrew Scripture by Matthew. If the passage from Isaiah as a whole (its preceding lines in particular) refers to the piercing, crushing, and punishment of the "suffering servant" ... how is the 'tail-end' applicable to events that happen beforehand? Sketchy arguments about 'retrospective effect' loom....

The reader is challenged to peruse John Wesley's A Plain Account of Christian Perfection and emerge anything other than ... entirely confused. It is certainly not 'plain'.

See D.E. Harrell, All Things are Possible: the Healing and Charismatic Revivals in Modern America (Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 1979)

See D.E. Harrell, Oral Roberts: an American Life (San Francisco CA: Harper & Row, 1985)

See C.D. Weaver, The Healer-Prophet: William Marrion Branham (Macon GA: Mercer University Press, 2000)

Excellent! Very familiar (and still unsettling because of sometimes-contradictory but deeply-ingrained assumptions) territory for many people who were raised in a conservative evangelical church context in the 1950s and 1960s, at least in the US.

Kept me under stress till the end.... :)) Did Jesus make some shows while healing? At least in Gadara...

Any connection between pigs and healing today? What about resurrection of Lazarus?