Obviously, I have no idea whether Bob Dylan was underspanked as a child. But he was definitely underspanked as an adult. Not that the fact detracts from the genius of his music, nor from the irresistibility of his early career as the subject for a movie.

A friend had expressed some surprise upon hearing of my intention to go and see this latest production, "A Complete Unknown" — well aware of my longstanding scorn-bordering-on-contempt for 'slebs', and my utter disinterest in knowing anything about them and their (usually sordid) doings. But, I explained with as much conviction as I could muster, Dylan was an exception: I had always loved his music, and in any case I wanted to see how the film-makers would portray the early 1960s.

Film-makers, as we know, have an even worse record than the worst historians in cutting out the past in the shape of (their preferred version of) the present. As with fiction writers, they get to choose who are the goodies, and who the baddies; the characters we will warm to, and those by whom we will be repelled; which historical phenomena will be portrayed favourably, and which unfavourably. They get to add scenes and exchanges that never happened, the better to score their points. (Indeed, the execrable "Darkest Hour" [2017] consists of little else.)

However — or so I reasoned — for a period as recent as the 1960s, years which remain indelibly etched on the minds of the generations that experienced them, the revisionists' room for manœuvre would be severely limited. Too large a slice of any audience retains the power to contradict any back-projected nonsense.

And having now seen the film in question, I think that surmise was about right. I do not feel manipulated. Indeed, I suspect my negative judgment on the principal protagonists would not be shared by the producer or actors — which is testament enough to their good faith on this occasion. It seems to this viewer that they presented the closest verisimilitude they could, and were rather enamoured with what they portrayed.

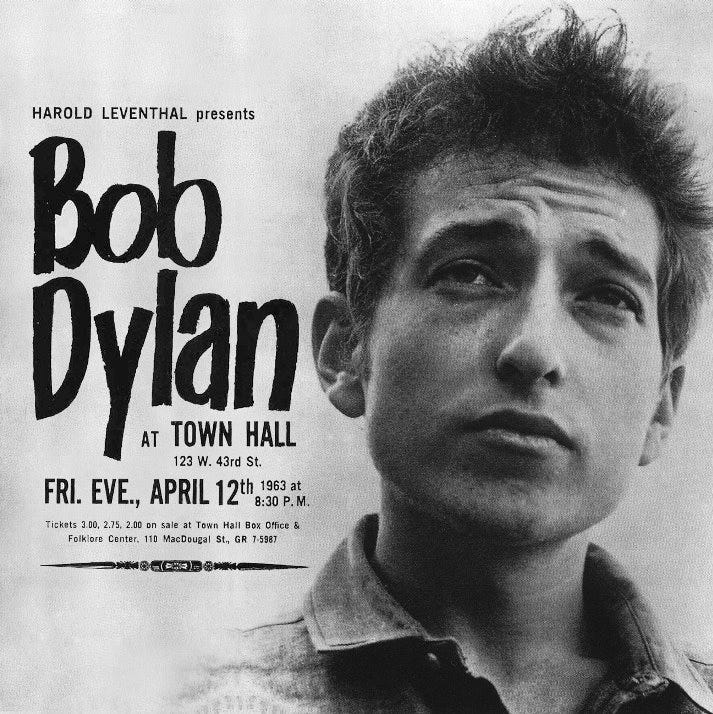

To start with the innocuous: Bob Dylan; Joan Baez; Johnny Cash are universally known by both sight and sound; replicating their appearance and their singing was always going to be a tough call. Admittedly, many have successfully imitated the lead character's voice; my own son has, on occasion, managed to sound more like Bob Dylan than Bob Dylan. But the young Joan Baez had a voice that could melt a glacier in the time it takes to boil a kettle; outside of opera (which she also sang), there has never been anything to match her. Both Timothée Chalamet (playing Dylan) and Monica Barbaro (Baez) are attractive enough, though neither is as good-looking as the principals they portray. (But there again, Joan Baez was in a class by herself.)

The film begins with nineteen-year-old Dylan arriving in New York in 1961 as a lad from Minnesota, in awe of his heroes, the left-wing folk singers Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. The former is already incapacitated in hospital; but the latter gives young Bob an entrée into the folk circuit, a group that included the newly-famous Joan Baez — and his rise from there is meteoric.

The movie draws out the original subversion of his lyrics — a subversion that can too easily pass us by, as both the words and the sentiments they enshrine have become so familiar to us as to be commonplaces. But when he sings:

"Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don't criticize

What you can't understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is rapidly agin'

Please get out of the new one

If you can't lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin' "

... the crowd stands and roars its support. And one suspects the film's producers think we should, too. I, however, shuddered and cringed.

The full — nay, long overdue — justice of the civil rights movement notwithstanding, the 1960s saw the advent of a spoiled, self-righteous generation that sneered at its parents for providing them with comfort, saving them from fascism, and shielding them from communism. Dylan's youthful, down-at-heel, street bum appearance was — as with most of his tribe in the two centuries and more since Rousseau — a choice and an affectation. (Go look up his early life on Wikipedia. Look at the picture of his childhood home.)

My main takeaway from the movie is how horrible most of the main characters were to one another. On this showing, only Pete Seeger and his Japanese wife Toshi appear (their obnoxious politics notwithstanding) to have been utterly decent human beings. Dylan, Baez and the others, however, were the true makers of the 1960s generation — for whom the 'correct' social and political outlooks served as substitute for morality, and absolved their advocates from actually treating people, including one another, with elementary decency and consideration. As I indicated earlier, it seemed to me that the film-makers were just fine with all that — but then, this disposition has long since become the default outlook of our politicians, entertainers, and what we laughingly call 'thought leaders'.

Dylan's behaviour on-stage is, at several points, disgraceful. He and Baez alternate from giving one another the finger (shielded from the audience by the guitar) ... to having sex ... to another bust-up.

The dénouement is an event that I recall hearing about as a child: Dylan outrages his friends and the organisers of the Newport Folk Festival by playing electrified rock music — eliciting cries of "Judas!" from the fans, and leading to fisticuffs back-stage. (Too bad that this act of jeering disrespect to those who have made his career includes the magnificent "Like a Rolling Stone".)

A good movie? Definitely. But one worth seeing with an eye to the rather contemptible present that a selfish generation has bequeathed us.