Is there such a thing as “a biblical worldview”?

Is there such a thing as “a biblical worldview”?

Yes.

Is there such a thing as “the biblical worldview”?

No.

Let me explain:

“The Biblical worldview” is, in actual practice, the rhetoric used by many Reformed Protestants, who are (mistakenly) sure that they represent the central, historic strand of Christianity, from which everything else is a deviation, either more tolerable or less, as the case may be. This generally becomes apparent as their expatiation proceeds: they always refer to the same figures. Augustine (who, in their view, counts as 'Early Church' — never mind that he was upending all that had gone before); then perhaps (if they're feeling generous) Pope Gregory I; and then, of course, Luther; Calvin; the Puritans.

Of course, the current incarnation of this supposedly normative strand is far from what Calvin and his fellows would have recognised or approved — for it is shot through with the assumptions (religious pluralism; democracy; capitalism) of the modern Westerners who form the Reformed constituency today, rather than in the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries, but which is nevertheless presented as “biblical”. (A slight exception would be the mercifully small, nutjob version of this viewpoint connected with Rousas J. Rushdoony (1916-2001) — whose aspirations ran at least closer to what his historic mentors would have approved.)

I am not sure of the point — and would welcome correction — but I suspect it was Francis Schaeffer (1912-84) who, if he did not coin such language (“the Biblical worldview” etc.), at least popularised it. The highly systematic nature of his favoured brand of theology — centred as it is on three or four mutually reinforcing axioms — perhaps lends itself to rhetoric about a ‘worldview’.

Few other Christians talk this way — or else they use more cautious terminology. C.S. Lewis, for example, spoke of “mere Christianity”, to refer to the things that almost all Christians held in common.

In practice, too many people who speak of “a biblical worldview” — and almost all those who speak of “the biblical worldview” — are those who are certain that this is a commodity upon which they and their particular faction have a corner. And this circumstance is unfortunate. While I have no desire to rescue the second expression, the first expression could be, and should be, rescued.

For just because “the biblical worldview” is a mistake does not mean we cannot speak of “a biblical worldview”.

Just because much in scriptural interpretation is debatable does not mean that anything goes — that anyone's view is as legitimate as any other.

Antebellum Southern white Christians, for example, often justified race-based slavery, using the Bible to do so. And their descendants down to the 1960s, like the Dutch Reformed Church (which was the mainstay of the South African apartheid régime down to the 1990s), used a modified version of such arguments to uphold racial segregation. No one at all has ever read Genesis and thought to themselves: "Of course! This means black people must be subjugated by — and certainly segregated from — white people!" It is a reading (if that's not too generous a term) that one would have to be very carefully schooled in to find remotely convincing. It is the elementary distinction between exegesis — reading out of a text — and eisegesis: reading into it what you already wanted to find there.

Now, despite the endless repetition to one another of such 'biblical' arguments (and, in consequence, the proliferation of subsidiary arguments to the same end), it would not be too difficult for you or me, given an endless supply of patience with such racists, to dismantle the biblical legitimacy of such a case.

In other times and places, various groups have used the Bible to expound views which, over 2,000 years of Christian history, have been shunned as heresy.

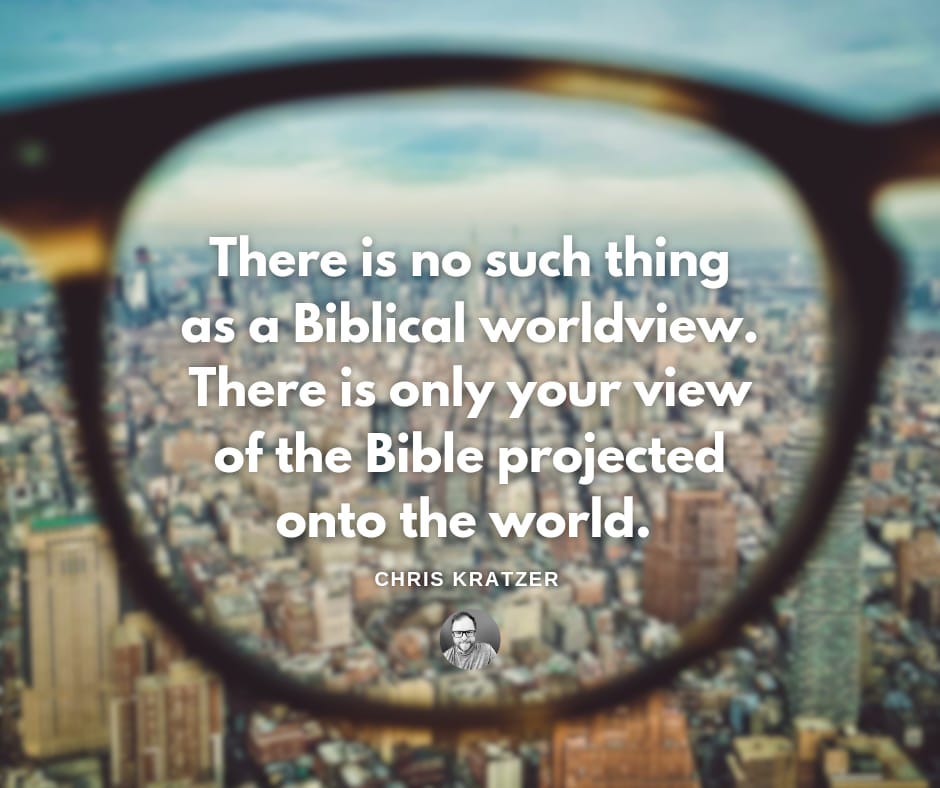

But the Bible does not, and cannot, mean just anything. And in this, at least, it is no different to any other text — including this one. And including Chris Kratzer's meme, above — which goes, imho, far, far too far. Not even he really means what he says, for if a text can mean anything, he would have remained silent.

What we have, then, when confronted by the Bible, is a range of plausible hermeneutical options. And once one is chosen, then certain conclusions are likely to follow. All of the plausible options will exclude rather a lot of conclusions. (You cannot, for example, contrive to get five gods out of a reading of the Bible.)

Within such parameters, then, is a broad — but still clearly defined — area we can call orthodoxy ... or “a biblical worldview”.

'Sola scriptura' may be a delusion — for no one comes to the Bible with a mind that is a tabula rasa. (With the possible exception of my freshman students!)

Tradition

Certainly, the Protestant Reformers did not do so: their minds were marked with the imprint of Augustine; with very many of the assumptions of mediæval religion (they set out, after all, to reform Christendom — not to abolish it); and with a strong desire (admittedly less marked in Luther than in Zwingli and Calvin) to square their version of 'the clear teaching of Scripture' with ancient Greek philosophy. For them, tradition mattered. Fundamentalists today may scoff at such stuff, but even they accept the doctrine of the Trinity — though the actual term isn't in Scripture, and wasn't coined until Tertullian did so ca. 200 A.D..

Reason

Certainly, the various attempts made to square one biblical teaching with another in some sort of system — an instinct I share, though ever more weakly with the passing of the years — reflects the concerns of modernist rationalism rather than strict biblicism. For, as all who have attempted this are very well aware, any overly systematic scheme of dogma is confronted with (How to put this gently?) problem verses at every turn. If God had wished to give us a book of systematic theology — rather than the Bible we actually have — then He surely could have done it. But He didn't. And yet, you notice, that doesn't stop us. Reason, apparently, matters.

“The Holy Spirit led me”

Many kinds of Christian — illuminist monks and nuns; mystics and visionaries; early Methodists and the Holiness tradition; Pietists; Pentecostals and charismatics — have emphasised the importance of seeking, and receiving, spiritual illumination. Almost all have made the disclaimer that what is thereby revealed to them must be subjected to 'Holy Mother Church' [Catholics] or 'scriptural authority' [evangelicals]; a very considerable number have, in actual practice, pushed against the boundaries of those limitations.

But none of this — tradition, reason, spiritual inspiration, and the ideas one has accrued simply from the wider society in which one has spent one's life — means that the 'conversation' between the self and its Sitz im Leben, on the one hand, and Scripture, on the other, is a one-way street. The Bible still speaks; still qualifies and changes what the reader thought before; causes tradition to be, at least, questioned; casts doubt upon our breezy rationalism; subjects to scrutiny whether our 'spiritual inspiration' passes muster or should be written off as a mere case of the goose-bumps.

And rightly so! The net result of all this — ideally, at least, though often in fact — is “a biblical worldview”. Not “the”: the distorting lenses are too many and too powerful to make any such claim. But at least “a”: despite all the variables, there remains a core orthodoxy we can find in Scripture. It will be what the fifth-century monk Vincent of Lérins called “that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, and by all”. It will be what C.S. Lewis called “mere Christianity”. And in an age that has abandoned truth, this really, really matters.