How Foxe's 'Book of Martyrs' has Shaped Us More than We Know

A short study in the evolution of popular thought

Introduction

The man

The book

The impact I: Anti-Catholicism

The impact II: Religious individualism

The impact III: Nationalism

The impact IV: Unstable eschatology

The impact V: Bloody-minded moral defiance

Introduction

From the late sixteenth century through to the early nineteenth, no book except the King James Bible was more widely read among English speakers than John Foxe's famous magnum opus. Seventeenth-century English people and American colonists, in particular, imbibed its ideas with their mothers' milk. And, though its overwhelming impact on our patterns of thought is now mostly unconscious, among 'hot-Prot' types the conscious element has endured down to fairly recent times.

Every week since 1942, BBC Radio has broadcast a show called 'Desert Island Discs'. "If you were cast away on a desert island, which eight gramophone records [yes: 1942...] would you choose to take with you?" Heck, I'm typing this from memory: that's how often I've heard the incantation.

The show was a new twist on interviewing some famous person — politician; author; actor; or mere 'sleb' — to tease out their personal lives. At the end of the show, they are asked to say what luxury item they would choose to have with them, and which book. In the early years, far too many chose the Bible and Shakespeare, so the rules came to stipulate that those works would always be there — so which other book would it be?

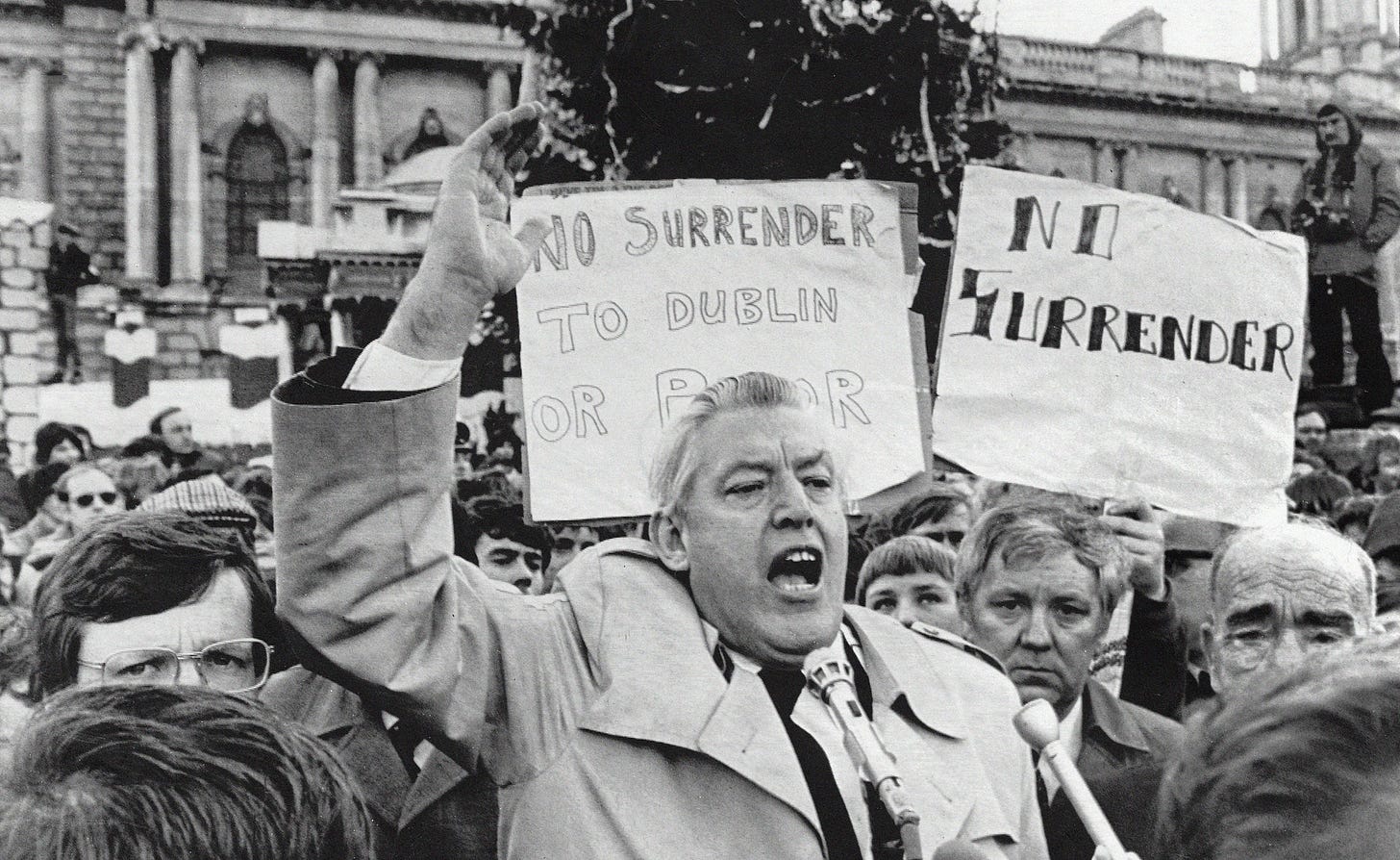

At some point around 1990 or so (I forget when), the Ulster preacher and politician Ian Paisley was the guest of the week. This was the man who had galvanised hardline Protestant Loyalism; whose slogans were "Home rule is Rome rule!" and "Ulster says: Never! Never! Never!"; who had protested the visit of Pope John Paul II to Britain in 1982; and had interrupted a speech by the same pope to the European Parliament in 1988 by shouting "I denounce you as the Antichrist!" And without hesitation, I guessed at once which book Paisley would choose to have with him on his desert island — a location which not a few of the listeners would heartily have wished upon him.

One might argue, of course, that I was wrong to 'stereotype' the man. But I would counter that, on the contrary, if a person has spent so much time and effort to tell the world who they are and how they wish to be perceived, then — as with the self-disfigured gargoyle in line behind you at the supermarket — it is more respectful to believe them.

And anyway, I was right. Even with only himself for company and little hope of rescue, Paisley would have chosen John Foxe's Actes and Monuments of the Christian Religion (to give the 'Book of Martyrs' its proper title), the better to lovingly nurture his detestation of Roman Catholicism.

If, in all this, Paisley was reflecting the theological tenets of his sixteenth-century hero, he was nevertheless very far from the actual spirit of Foxe, whose work was one long protest against religious persecution as much as a critique of the Roman Catholic Church. Nevertheless, as we have seen in our own time, the book's potential for truculent and violent interpretation was certainly there.

The man

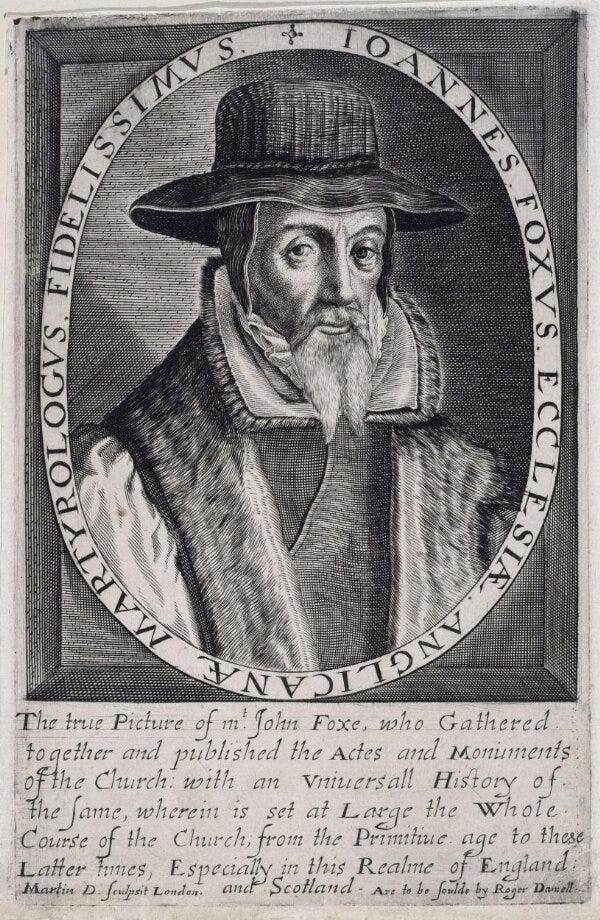

John Foxe (1516-1587), martyrologist and moderate English Puritan, was born at Boston, Lincolnshire and educated at Oxford, where he was a fellow at Magdalen College (1539-45). He married Agnes Randall in February, 1547.

He held several positions as private tutor during the later years of Henry VIII (reigned 1509-47) and the reign of the Protestant boy-king, Edward VI (1547-53), and was ordained a deacon in 1550. But on the death of King Edward, Foxe went into exile to avoid the re-Catholicisation policy of the new queen, Mary, and its attendant persecution. He had in any case been dismissed, as a Protestant, by his employers, the Catholic Howard family.

It was this exile which was to be the making of Foxe’s career. Already interested in Christian history as a result of his friendship with John Bale (1495-1563), the scurrilous Protestant pamphleteer and Edwardian Bishop of Ossory, Foxe turned his attention to accounts of Christian martyrdom, both past and present.

He also joined with the English refugee congregation at Frankfurt-am-Main by late 1554, and participated in its celebrated ‘troubles’ the following year, in which he sided with John Knox’s more stern, austere faction.

After the 'troubles', that faction removed itself to Calvin’s Geneva, but Foxe moved instead to Basel, where he continued his writing. The following year, he published an apocalyptic drama, Christus Triumphans, followed in 1557 by another Latin work, pleading for an end to the persecution of Protestants in England.

Unlike almost all of his contemporaries, however, Foxe was opposed to persecution (or at least to lethal forms of it) per se, rather than merely to the suppression of his favoured brand of religion.

It should be underscored that the Reformation did not bring in — nor aim to bring in — religious toleration of any kind. On the contrary, it sought to replace the Catholics' 'wrong' religion with its own 'right' one. That is why the Reformation-era conflicts over which faith actually was the correct one were so bloody and protracted. So on this subject, Foxe was out on his own.

He was later, in 1575, to plead with the Protestant Queen Elizabeth for the lives of Dutch Anabaptists whose views he abhorred, and at least one historian has argued that he had done the same — with equal lack of success — for Joan Bocher, who was burned by Edward VI’s government in 1550. If Foxe was highly unusual in this respect (for one who was not himself a religious radical), it was perhaps his subject matter that had helped him to see something that none of his Protestant peers could.

Despite Queen Mary’s death in 1558 and the succession of her Protestant half-sister Elizabeth, Foxe did not immediately return to England. Instead, he remained in Basel to complete — at least for the time being — his martyrology, which was published there in Latin the following year as Rerum in Ecclesia Gestarum.

In the autumn of 1559, he finally returned, and was ordained by his friend Edmund Grindal (now the new bishop of London) in 1560. His objection to wearing the surplice, the symbolic target of the infant Puritan movement as representing ‘the rags of popery’, meant that he could not hope for high ecclesiastical position. Though he was eventually given a stipend as prebend of Salisbury Cathedral, he spent the rest of his life in London, working on extensions of his magnum opus.

The public records were thrown open to him, and all who had personal knowledge or experience of the Marian persecution of Protestants were encouraged to submit their documentation to Foxe. The first English edition of the Actes and Monuments, generally known as the Book of Martyrs, appeared in 1563. It was a massive work, but the new edition of 1570 was larger still, running to two volumes of a combined 2312 pages. The 1576 and 1583 editions contained yet more material. The last of these was the final version to be published during Foxe’s own lifetime, and he died in 1587, being buried at St. Giles, Cripplegate in London.

The book

It is almost impossible to exaggerate the influence of Foxe’s work upon the English national and religious consciousness during the following three or four centuries. In Stuart England, only the English Bible was more widely read, and no literate person — and few illiterate — was unfamiliar with its themes and stories, or untouched by its outlook.

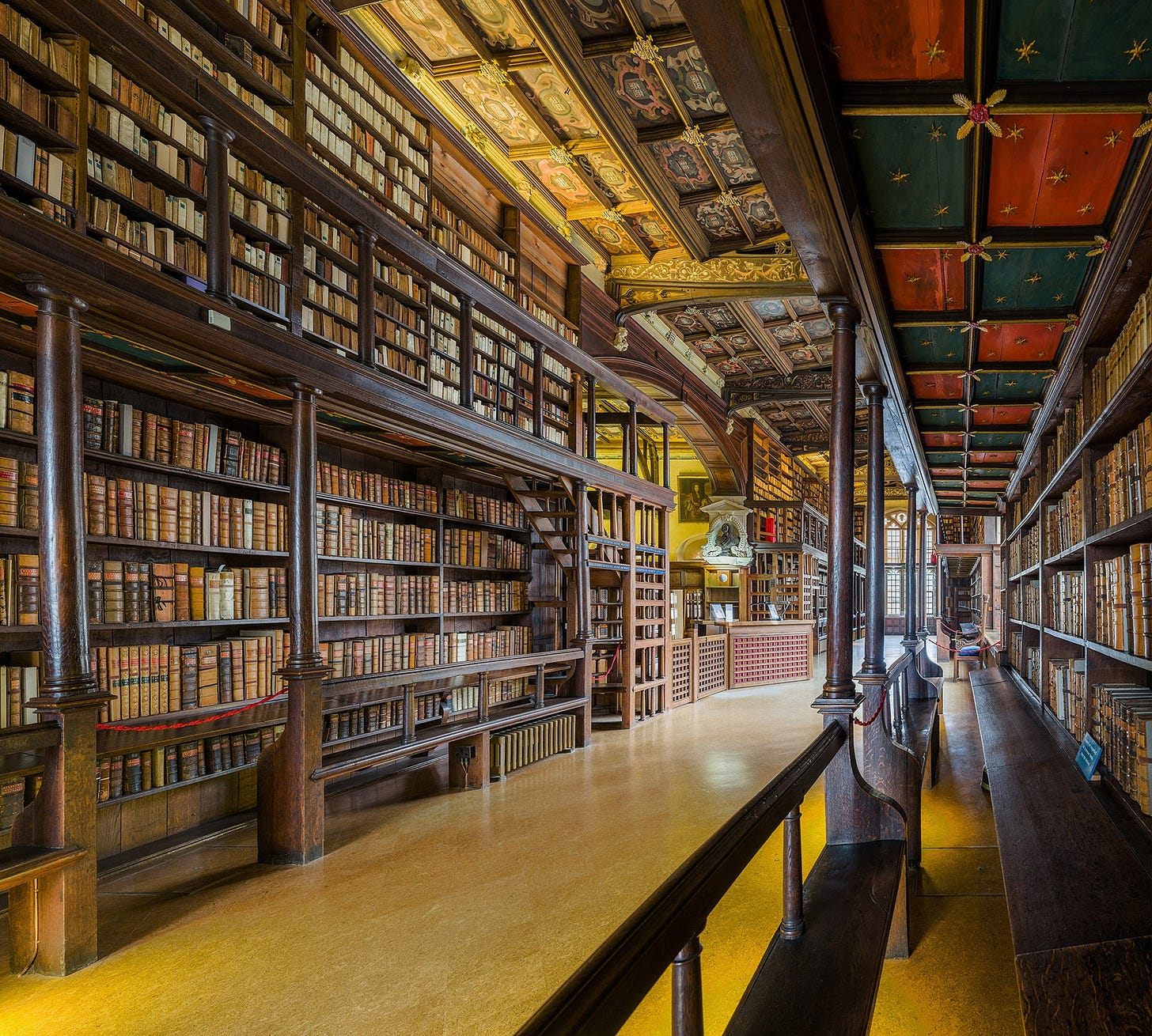

As it happens, I had frequent cause to have recourse to this gigantic work during my own doctoral studies, and had access to sixteenth-century originals (now available online here) in the Duke Humfrey Library — the oldest part of the Bodleian — which is used for the storage of mediæval and early modern manuscripts, and early printed books. (One is not, of course, allowed to take them out of the library but, for the ongoing researcher, they are put aside behind the main desk and handed to you afresh on your arrival each day. To be recognised by the desk staff and to have one's books passed over is a ritual that gives the sensation of belonging to one of the most exclusive clubs in the world — which is exactly what it is.) When one remembers that the most recent edition of the work (we pass over with scorn the ridiculous paperbacks passing themselves off as such) was published in 1870 in eight very large volumes ... and that the Elizabethan original was published as a single, enormous volume ... one can have some conception of how great was the combined anxiety about weight and ancient fragility, even for so simple a task as moving it from the main desk to one's own work bench.

The Book of Martyrs gives a catalogue of Christian martyrdoms from the earliest times of Christianity down to Foxe’s own day. The first sections, therefore, provide well-known accounts of early church martyrdoms. In covering the Middle Ages, however, Foxe is at pains to stress the persecuting nature of the official — and of course Roman — church itself. In covering the late mediæval period, his more specific polemical purpose becomes clear. Most of the martyrs are English Lollards, the followers of John Wycliffe (ca. 1329-1384), who might, at a pinch, be seen as Protestants avant la lettre.

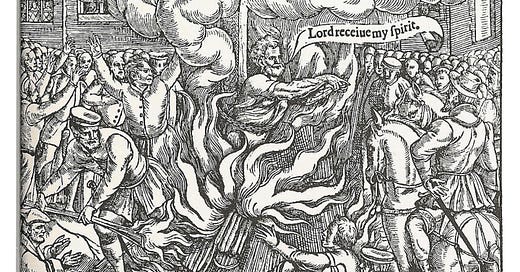

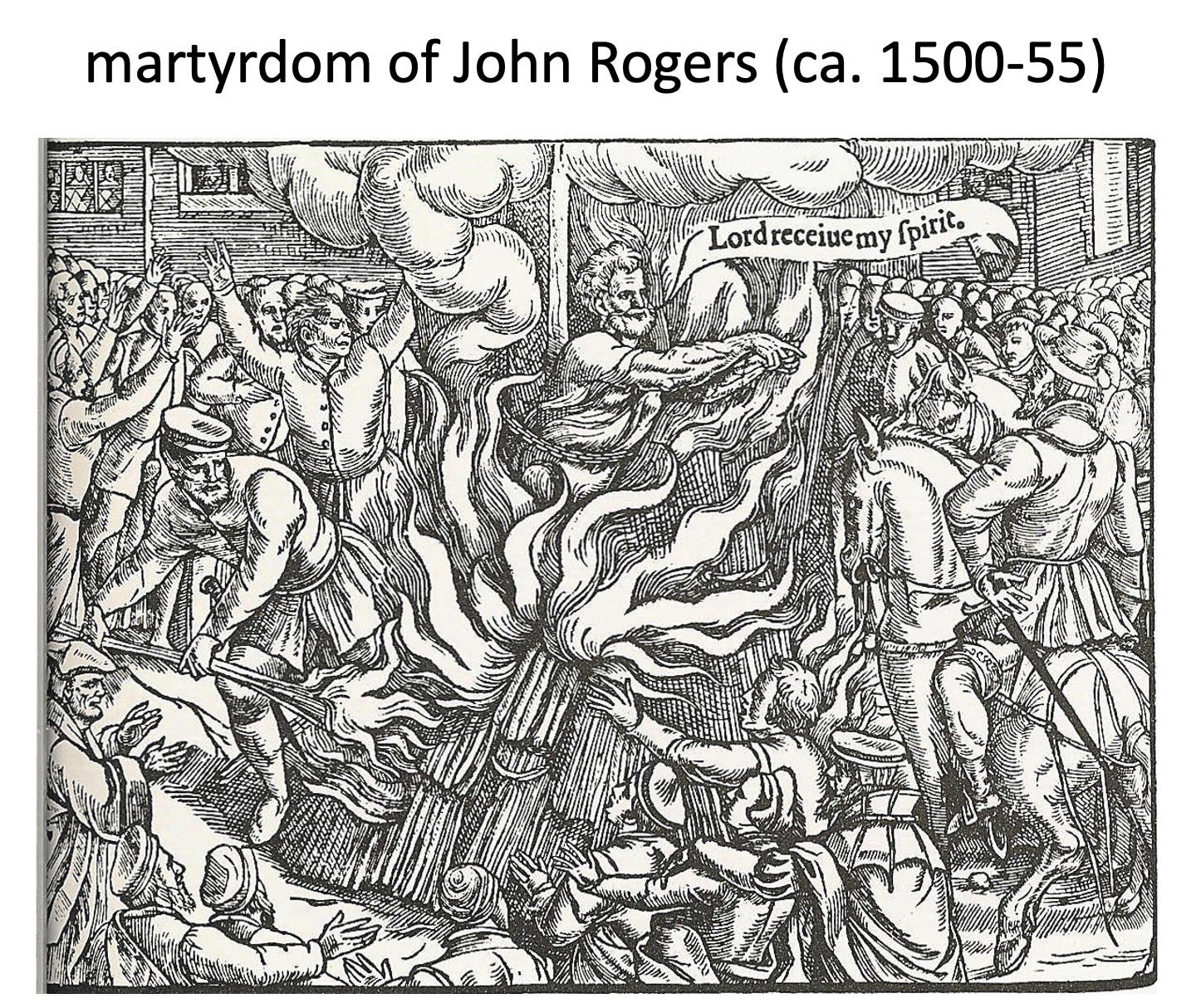

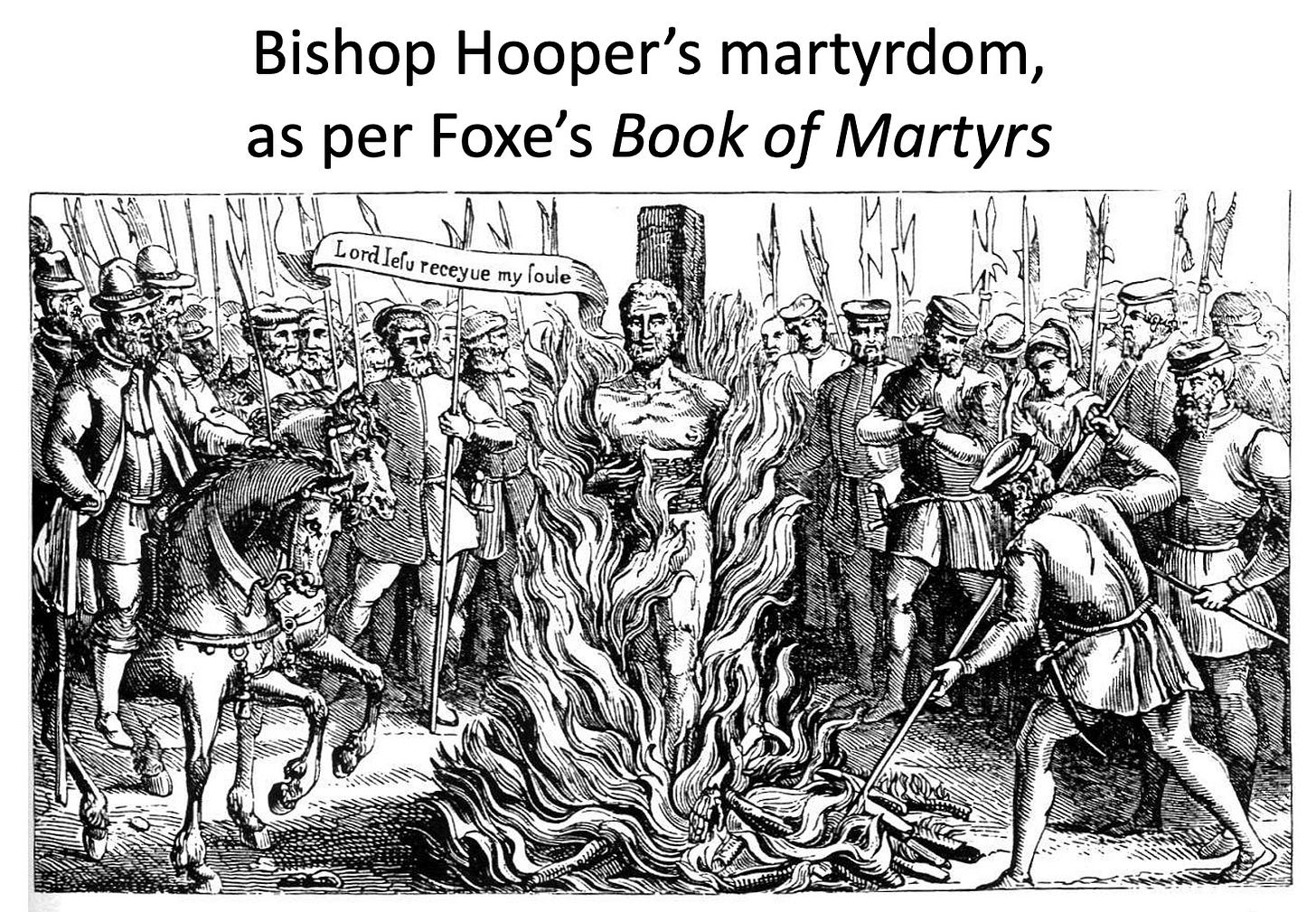

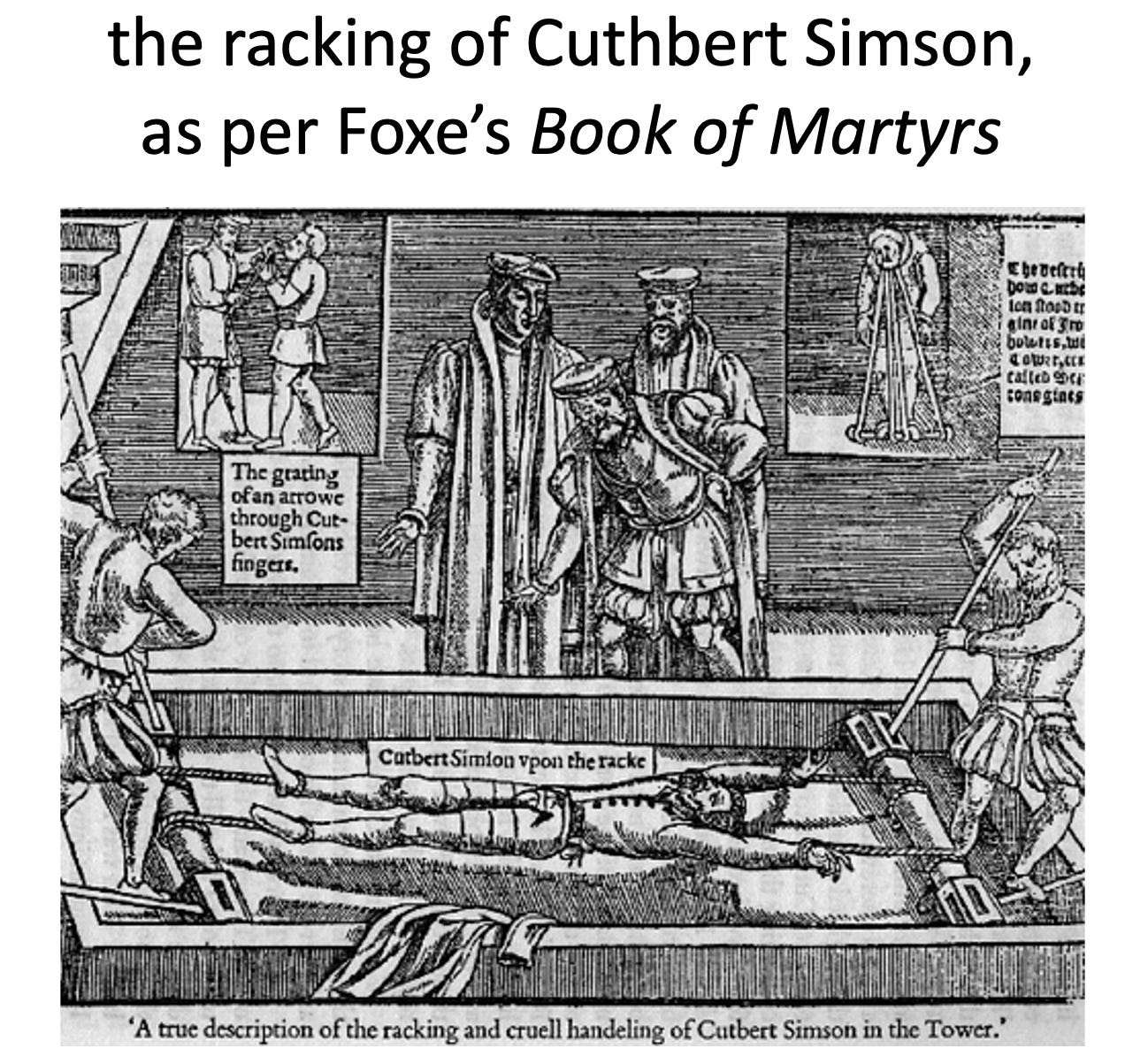

The culmination of his work, however, is the exhaustive accounts of the Marian persecution of Protestants of 1553-1558. Foxe supplies countless narratives of the interrogations and correspondence of the prisoners — both those who were martyred and those who, for one reason or another, were spared. In this, he is both copious in factual detail and polemical in his comments. His arch-villain is Edmund Bonner (ca. 1500-1569), the Marian Bishop of London (‘bloody Bonner’, ‘bite-shepe Bonner’).

No one could plausibly argue that Bonner was a nice man. Indeed, he was a brute. But he was not quite the ogre, thirsty for Protestant blood, that Foxe painted him. Indeed, his very rough and aggressive tactics with prisoners seem to have been designed to scare them into a minimal recantation — and acceptance of the Catholic doctrine of transubtantiation sufficed to count as such — that would give him a sufficient excuse to eject them from the prison cell and out onto the London street. In that, Bonner was not atypical of the enforcers of official conformity down the ages — but typical. What was wanted was not victims, but conformity. And conformity yielded between gritted teeth would do just fine.

Despite Foxe's obvious hostility to Roman Catholicism, he is generally a very reliable source in his accounts of the lives and deaths of his heroes, however much he colours them. (We are in a position to double-check most of what he tells us.) His propagandistic sins against strict accuracy are not generally sins of commission, but of omission. He is known to have left out details of individual cases which might have been damaging to the cause of state-church Reformed Protestantism. In particular, some of the prisoners whose stories he tells were, in fact, religious radicals, distant fellow-travellers with Anabaptism; but Foxe omits to mention key details in such cases, and sometimes coyly supplies only a person’s initials. (Fortunately for us, we often know exactly who he was really talking about!)

In addition to its vast general influence upon English society, Actes and Monuments injected five major elements into English popular thought:

The impact I: Anti-Catholicism

In the first place, generations of readers were left in no doubt that Roman Catholicism was inextricably bound up with sinister and vindictive religious persecution. To that extent, the all-pervasive influence of the Book of Martyrs played its part in shaping the visceral anti-Catholicism that marked — or scarred — English life down to the early twentieth century.

Foxe was writing during the period of formation of the 'Black Legend' — the picture of Counter-Reformation Catholicism as persecuting, devious, murderous, and unbending, with a preference for killing those whom it could not rule and for torturing those whom it could not persuade. The Legend's composite elements were, inter alia:

the Spanish Inquisition;

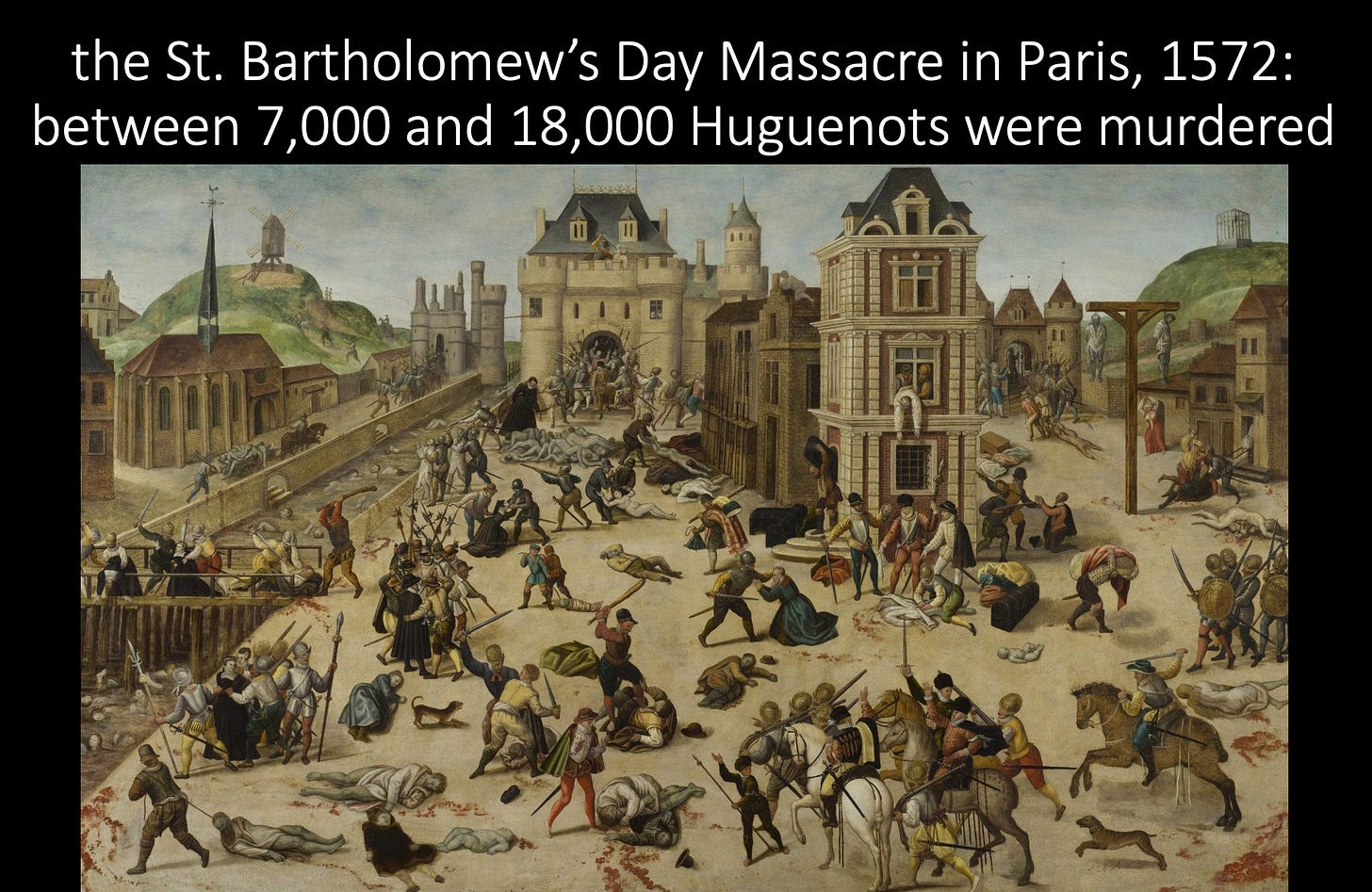

the 1572 Bartholomew's Day Massacre in Paris (in which Catholic zealots killed anywhere from 7,000 to 18,000 Huguenots);

the 'Spanish Fury' in Antwerp in 1576 (when troops killed perhaps as many as 30,000 civilians); and

the Armada of 1588.

And the Marian persecution of Protestants in England (with roughly 300 killed) took its place in this wider picture.

It was the polar opposite of the criticism made when the Reformation had started in 1517. Back then, the problem with the Roman Catholic Church was that it was decadent, corrupt, frivolous, and not religiously serious. However, following the reforms of the Catholic Counter Reformation — especially those instituted by the Council of Trent — the later Protestant criticisms which the Black Legend enshrined were that the Catholic Church was far too serious, entirely un-frivolous. It was coming to eat your children.

And Foxe's lengthy history and polemic (for the Actes and Monuments was both) formed the centrepiece of the English variant of this discourse. Queen Mary's wildly unpopular marriage to Philip II of Spain had endangered England's independence — a consideration that was starting to matter in modern, post-feudal, incipiently nationalist conditions — and her zealous husband had reinforced her determination to reimpose the Catholic faith. It was, therefore — quite contrary to the way things had seemed under Edward VI — possible to paint that Church as un-English. It was bound up with foreign domination, religious persecution, and tyrannical rule.

This was an inextricable combination of ideas that would endure in the popular mind for centuries. It crossed the Atlantic with the Pilgrim Fathers and the Independent Puritans who followed them in the 1630s, and formed a commonplace of American discourse that remained easily strong enough to stop Al Smith's 1928 presidential campaign dead in its tracks. He was a Catholic: it was enough. Even in the nineteenth century, by which time Catholics could again participate in British public life, it was very noticeable that army officers who were Catholic were known for their patriotic remorselessness on campaign: they could never forget that they had something to prove.

The impact II: Religious individualism

In the second place, Foxe’s accounts of ordinary laymen and women taking action as plain Christians against what they saw as a godless government had a further, albeit unintended effect. They provided inspiration for a wide range of religious dissidents, beginning with the Separatists, to break with the Church of England and found new, pure (but illegal) churches. In so doing, they saw themselves as emulating the people whom Foxe held up for admiration, the Marian martyrs: people who refused to participate in Queen Mary's official, reinstated Catholic Church, and met secretly to worship in the way they thought right.

Though the explosion of English sectarianism — the proliferation of different dissenting churches — would not occur until the following century, it was Foxe's book which had inadvertently provided the justification. The individual conscience not only need not, but should not, submit to an ecclesiastical authority it deemed to be wrong and corrupt. The heroes who populate Foxe's pages were examples enough of that.

The impact III: Nationalism

Thirdly, Foxe supplies a specifically nationalist religious vision. Now, 'nationalist' is a dangerous and very frequently misapplied term. Until modern times, 'nationalism' — and the national consciousness upon which it is predicated — did not exist in any sense that would be close to our own experience. Indeed, most historians date (as I think, correctly) the French Revolution as being the birth of what we consider modern nationalism. Nevertheless, that conception of the self did not suddenly materialise in 1789. The economic, social, and cultural conditions that made it possible had been building for a while.

And it was in late-sixteenth-century England (at least, in the south and east) and the Netherlands where (for complex reasons we cannot go into here) that distinctively modern self-conception was coming into existence. Think of some of Shakespeare's speeches, such as that which he makes Henry V give to his men on the eve of Agincourt: sentiments that, in reality, would have fallen totally flat to Henry's armed peasantry of 1415 — but which were calculated to stir the blood of London audiences in 1600.

Similarly, the central themes of Foxe's book were that God has never been without his Englishmen who will serve the cause of the gospel, come what may; that Catholicism is a foreign creed (associated with Queen Mary's highly unpopular marriage to Philip II); that Elizabeth is a new Deborah (the Old Testament prophetess), come to lead the people of England, who are, in a sense, the people of God. This direction of thought, apart from giving English Protestantism a peculiarly nationalist slant, was to bear fruit in later centuries in bizarre (and, one might add, heretical) ‘British Israel’ theories. ("And did those feet in ancient time walk upon England's mountains green?" Nope! But Queen Victoria thought so.)[1]

The impact IV: Unstable eschatology

Fourthly, Foxe believed that Protestants would consummate world history in a successful crusade against the papal Antichrist. In so doing, he injected an element of apocalyptic instability into the normally very stable theology of the Protestant state church.

According to Foxe, Elizabeth was a new Deborah (the prophetess of the Book of Judges), who was to lead the people of God (or England; it made little difference) on a crusade against the papal Antichrist. Elizabeth, of course, was far too realistic to do anything of the sort, but the idea was to have interesting consequences long after Foxe and his queen were both dead.

Leaving aside the rather large (!!) issues of the practicalities of Foxe's idea (and he was far from alone in making such claims) and their highly dubious premises, the effect was to introduce an element of instability into English Protestant eschatology (theology of the end times) that would have enduring consequences.

The Early Church had held an eschatology which we would now describe as premillennialist, i.e., that human history would be interrupted by the Second Coming of Christ, who would usher in a thousand-year (so: millennial) reign of the saints on a new earth. Unsurprisingly, this fell out of favour from the fourth century, when Christianity was co-opted by the state. Henceforth, all official, compulsory churches (Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic and, much later, Protestant) were amillennialist, i.e., the 'millennium' spoken of in Revelation 20 was purely figurative, and referred to the present time. Christ would return at some point in the unimaginably distant future and, in the meantime, Christians should ignore it and get on with being faithful subjects. The Great Interruption was not welcome.

But Foxe's theorising threw the fat back into the fire. Perhaps the millennial reign of the saints might be brought in, not by the return of Christ, but by using a little muscle in the present. An element of instability was introduced into an eschatology whose whole purpose, for twelve hundred years, had been stability — to reduce the return of Christ to mere theory, far distant and scarcely capable of investigation, far less susceptible of being hastened by this-worldly action in the present.

The playing out of the consequences of Foxe's thinking on this point has been explored and expatiated upon by William Lamont's masterful 1969 study, Godly Rule: Politics and Religion 1603-1660. As Lamont makes clear, visions of this sort — crusades against the Catholic 'Antichrist' — strongly implied a worldwide triumph of the True Faith. But it was this direction of thought — the convergence of this-worldly kingdoms with the irruption of the eternal — which the amillennial state-church eschatology had always been designed to keep at bay.

It was Thomas Brightman (1562-1607) whose posthumous book, Shall They Return to Jerusalem Again? effectively developed a new eschatology on the strength of this crusading direction of thought. What we call postmillennialism, i.e., the conviction that Christ shall return after a millennium, meant that the Second Advent would be ushered in by a this-worldly triumph of the saints. The priority, then, was to bring in that worldwide triumph as soon as possible.

Published in 1615, Brightman's book had a powerful impact on the thinking of many English Protestants in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries — from the harebrained Fifth Monarchy Men of the 1650s and 1660s, who sought to seize power "For King Jesus!", to the more sober-minded theologians and evangelists of the mid-eighteenth century, such as Jonathan Edwards and John Wesley, who foresaw a converted world in which "the glory of God shall cover the earth as the waters cover the sea".

Foxe foresaw none of this. But the effects of his book had an afterlife of their own. And postmillennialism was one of them.

Indeed, the political philosopher John Gray thinks that postmillennialism was in turn largely responsible for the secular utopian ideologies of the Enlightenment. These, after all, postulated an attainable Kingdom of God on earth — but without God. While this intellectual parentage is not entirely incontestable, Gray's argument nevertheless has much to be said for it. Foxe, then, might be seen as the grandfather of modernist political ideologies — an ancestry that would at least have the merit of annoying the heck out of the modernist ideologues.

The impact V: Bloody-minded moral defiance

Finally — and this is closely related to our second point — the heroes of Foxe's pages are people who defied the public authorities to pursue what they thought was right.

This simple idea — the moral autonomy of the individual, vaunting his or her own judgment over what is being publicly required, and then acting on that conviction — has become almost an axiom within the English-speaking world. Everyone is familiar with it. It is the central cliché of novels, movies, and of ordinary speech, to the point where it is not even recognised as a cliché at all. The British call it 'bloody-mindedness'; the Americans call it 'cussedness'. But they are the same thing.

For it is a peculiarity of the Anglosphere. All the other trappings of modern, democratic thought — individualism; human rights; rule of law; freedoms of speech, association, and assembly: these are the common possession of the West as a whole. Germans, French, Italians, Croats: all are familiar with them, and have built them into the public and private fabric of their lives.

But this — the individual's propensity to set the judgment even of legitimate public authority at naught, as either incompetent, blind, morally corrupt, or all of these; and to follow through that assessment with action — this is distinct to the Anglosphere. More than the previously listed qualities of the West, and perhaps even as much as a shared language, it is what gives Brits and Americans, Canadians, Australians, and New Zealanders a shared mentality, and a sense that they truly understand one another.

And it comes from Foxe. His book crossed the Atlantic with the first English settlers: indeed, their very act of defiance in going to the New World to conduct their own 'holy experiment' unimpeded by English bishops is, in itself, pure Foxe — as they well knew. This way of thinking saturated the new continent and, in greatly secularised form, continues to do so today.

Australia and New Zealand were settled long after the purely religious impulse of the Book of Martyrs was spent. But by then, the secularised form of this pathology was so deeply ingrained that that rugged individualism simply crossed the globe with the settlers: it was just ... the way to be. And, as in America, the demands of settling a wilderness from scratch underscored its usefulness and rightness.

Since Foxe wrote, much of the world has become secular. Since the 1960s, the combined effects of the Second Vatican Council, the charismatic movement, and the demands of the culture wars, have caused Protestants and Catholics to put enmity away and (mostly) to embrace as brothers and sisters. No one is preaching armed crusades against Antichrist; and postmillennialism, though not dead, is largely confined to the nuttier denizens of Moscow, Idaho. But the utopian secular ideologies which postmillennialism (arguably) helped to spawn are sadly with us still. And the bloody-minded (or cussed) individualism Foxe presented as an ideal has perhaps never been stronger.

We are more Foxeian than we know. It came with our mothers' milk.

[1] For a fuller exposition on this subject, see chapter 6 of my The Gods of War (Downers Grove: IVP, 2007).